Body of Work: The Art of Eating Disorder Recovery

a sculptural diary

My career as an artist began when I admitted in my early fifties that I was a full-blown anorexic. Sculpture became a way to capture the emotional and mental bondage of my illness.

The first piece, Running on Empty, was a life-size paper tracing of my body. Elemental and primitive in motif, it explores issues underlying anorexia and the battle that raged deep within me. The composition exploded into a series of more than 100 sculptures, called Body of Work: The Art of Eating Disorder Recovery. Some pieces emerged spontaneously, almost recklessly, while other forms came to life gradually.

The collection is a brutally honest account and an emotive use of form. It “reads” like a gutsy and revealing sculptural diary. While the work depicts the passions, obsessions and rituals of life with an eating disorder, there is an urgency and universality to its scope. It speaks to the human condition well beyond the walls of often-misunderstood mental illnesses. Yet it transforms mental illness into an accessible, visual and visceral experience.

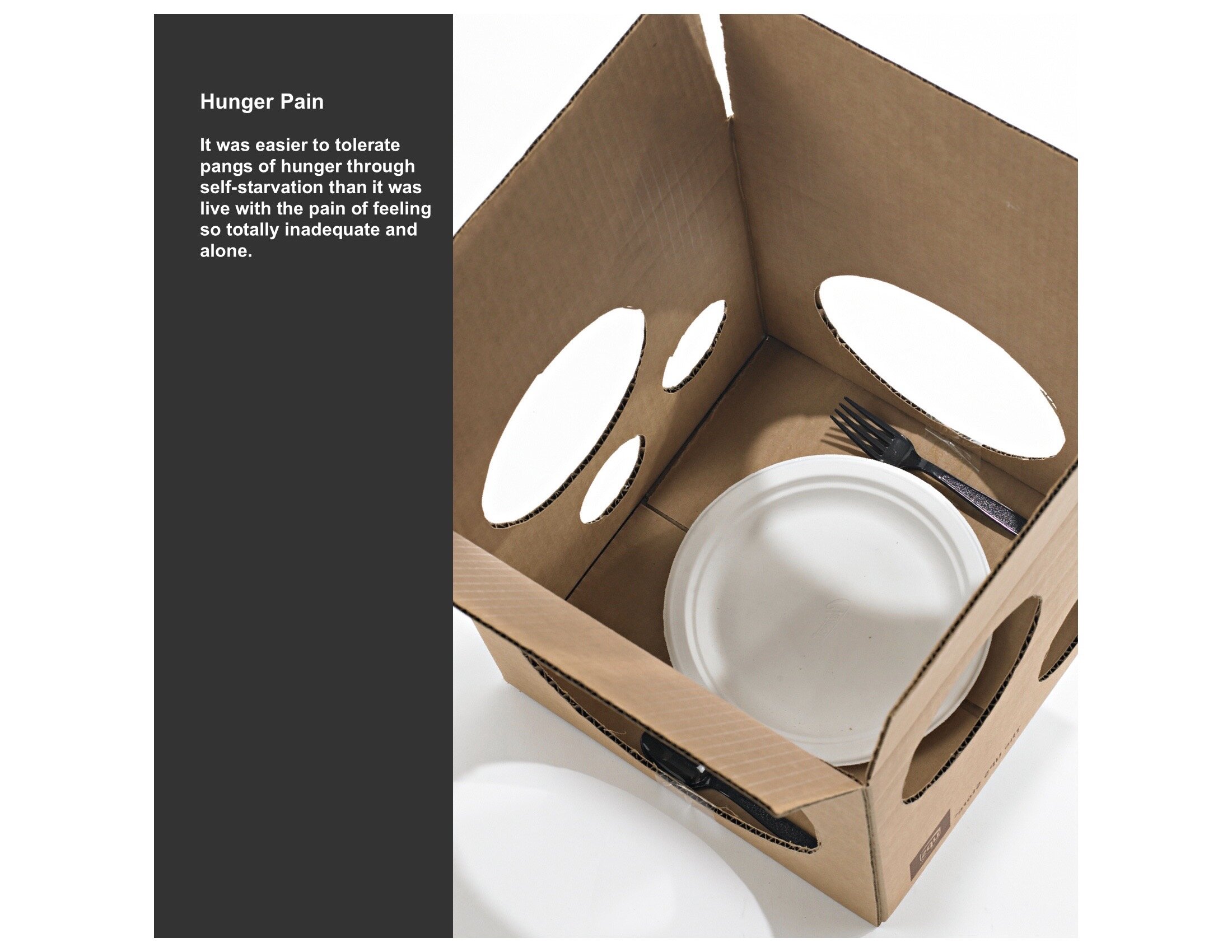

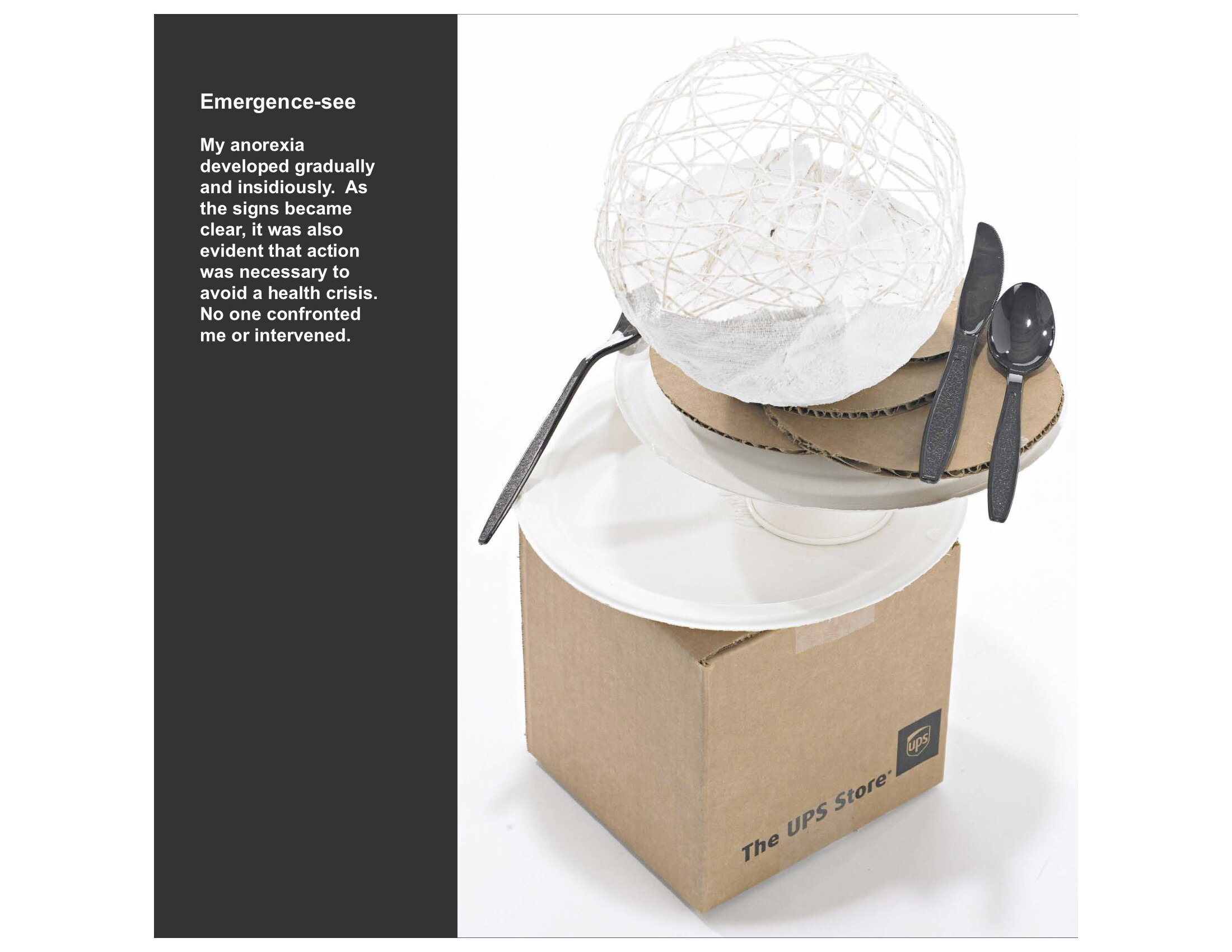

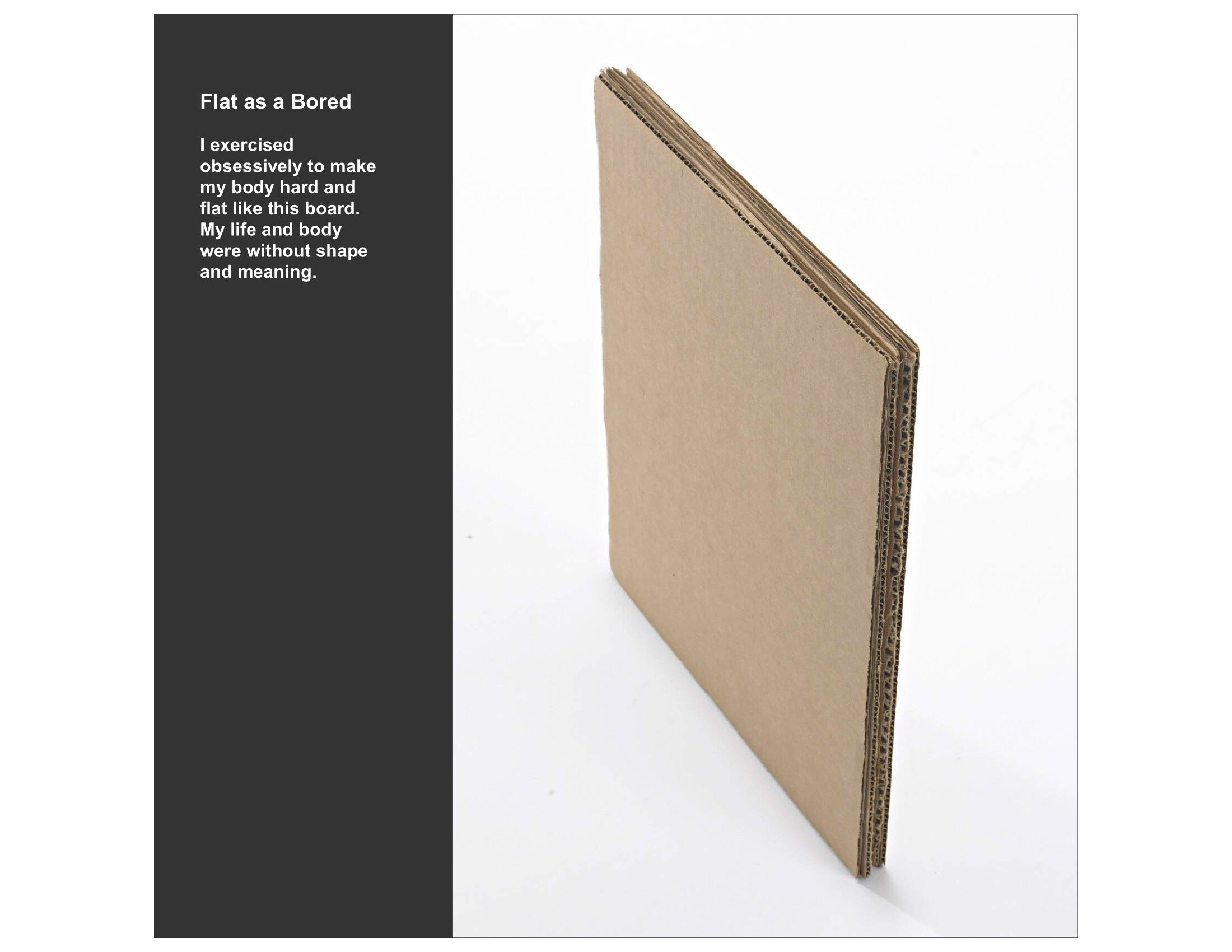

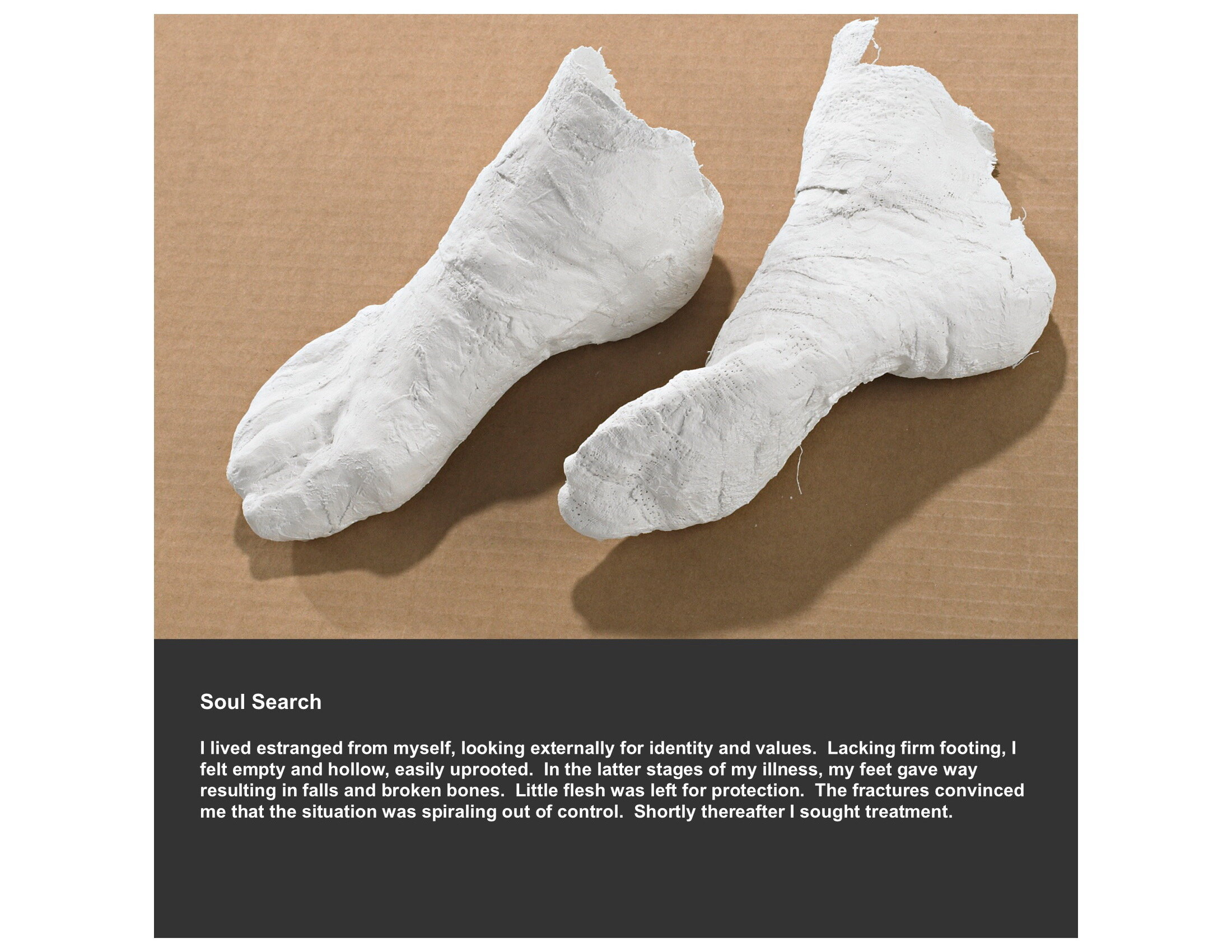

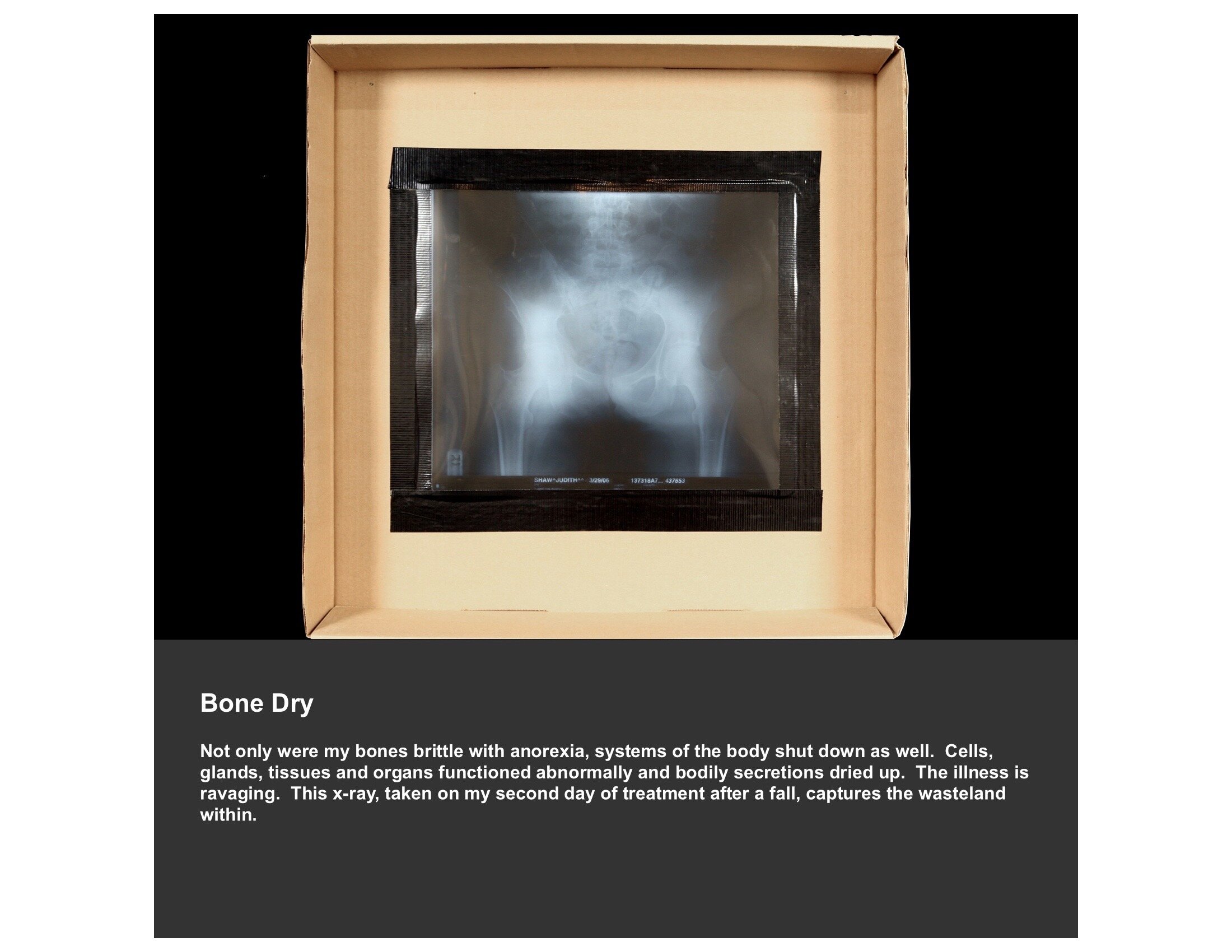

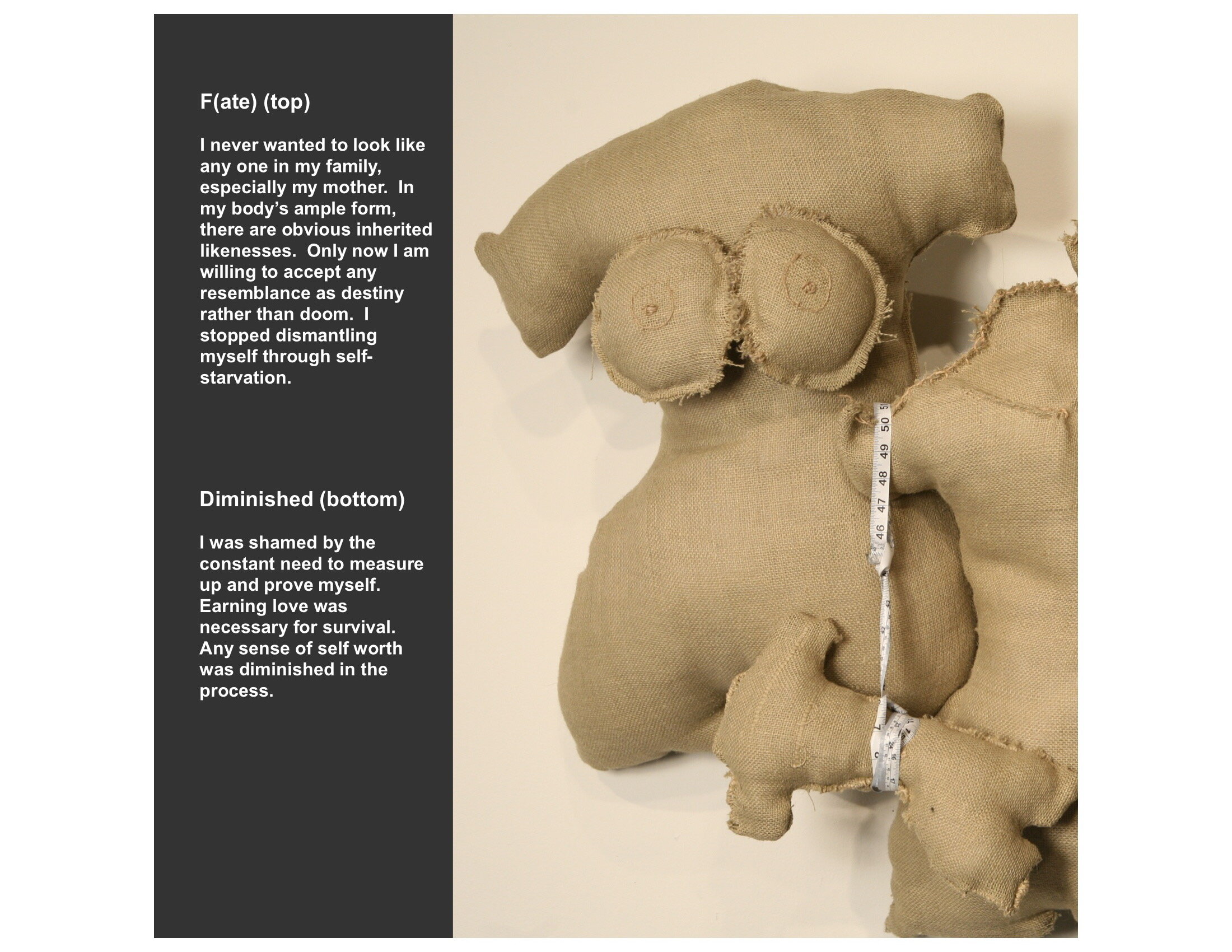

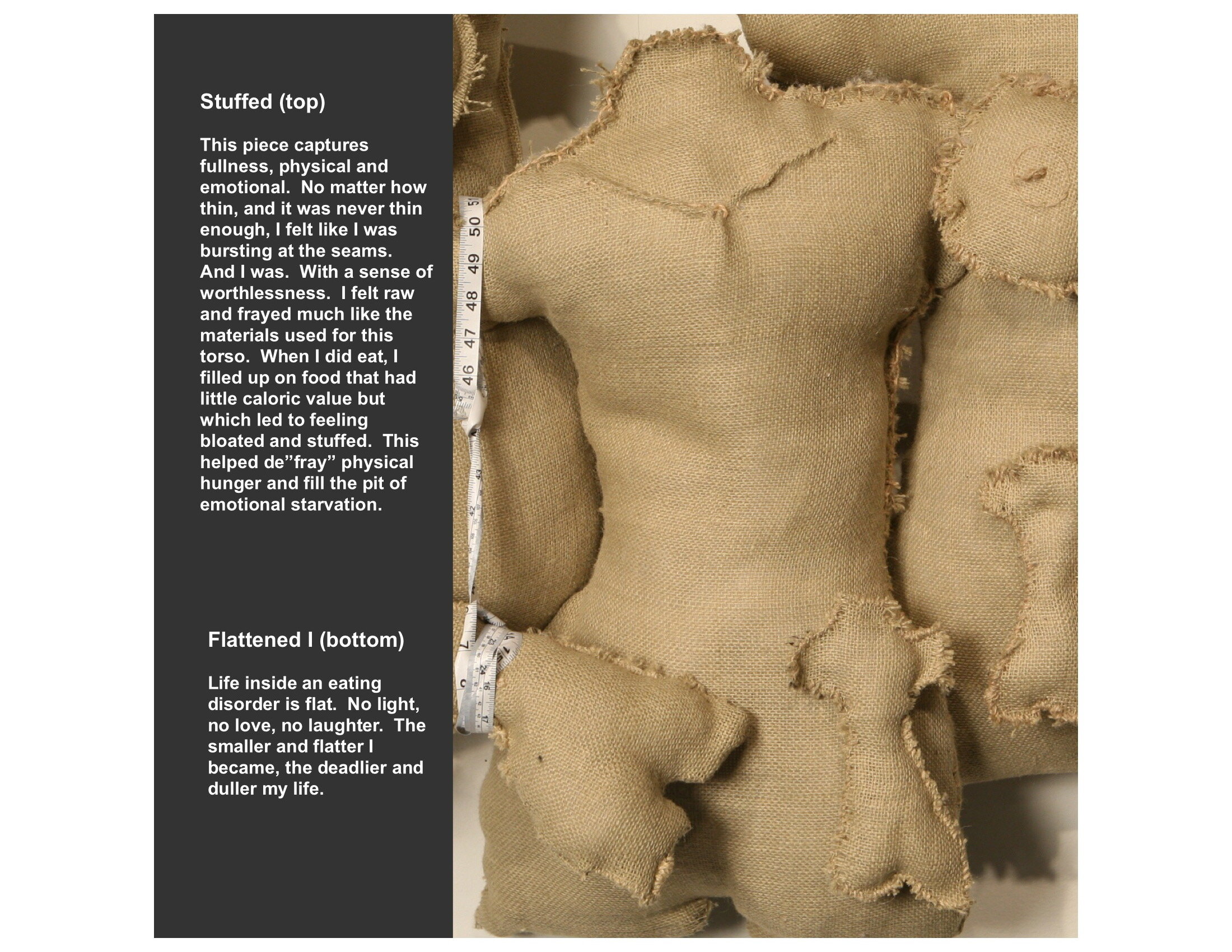

Assemblage-style forms from found objects and ordinary materials are fused with simple fabrication methods. Although many elements relate to food and eating, they offer layers of conceptualism and interpretation in a deeply human context.

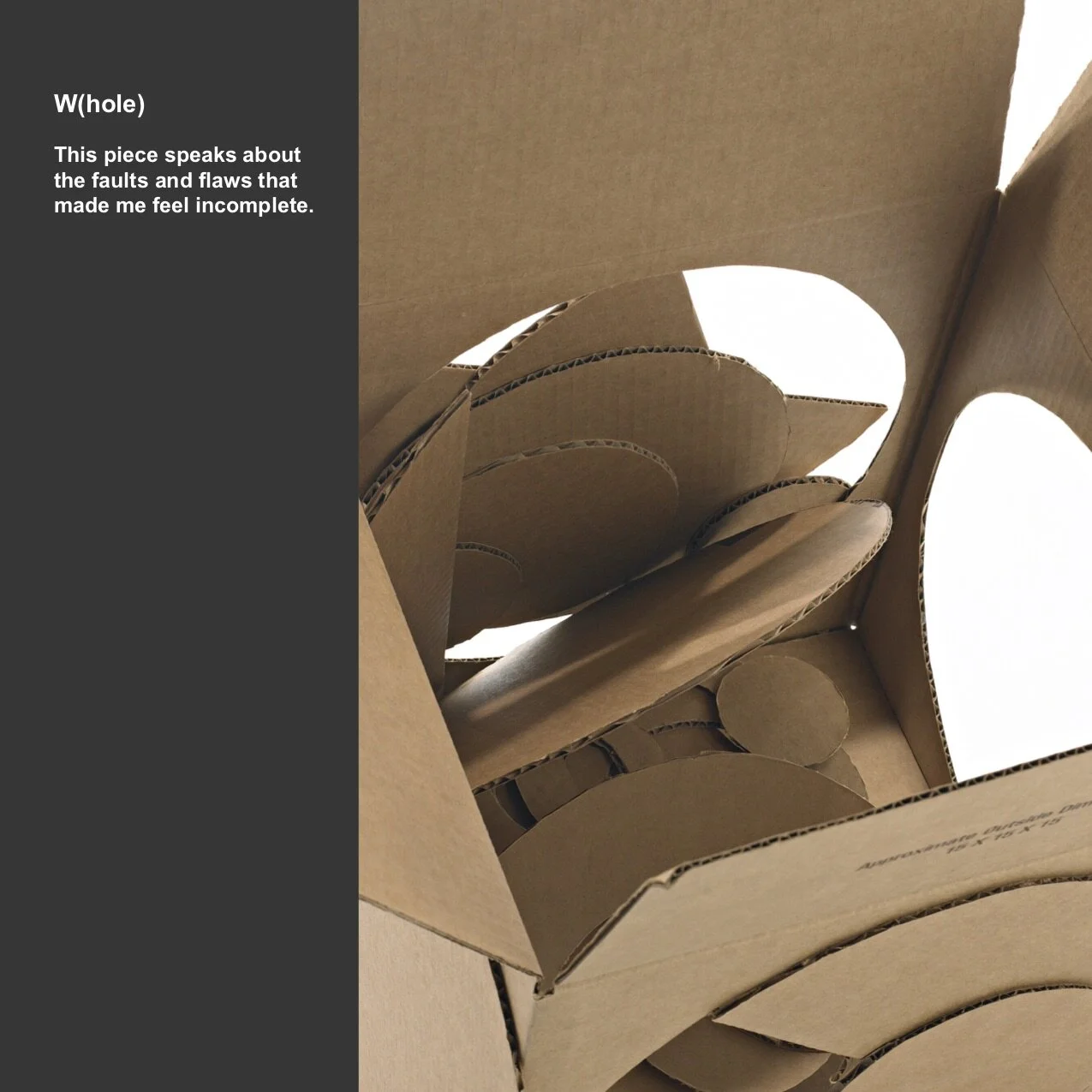

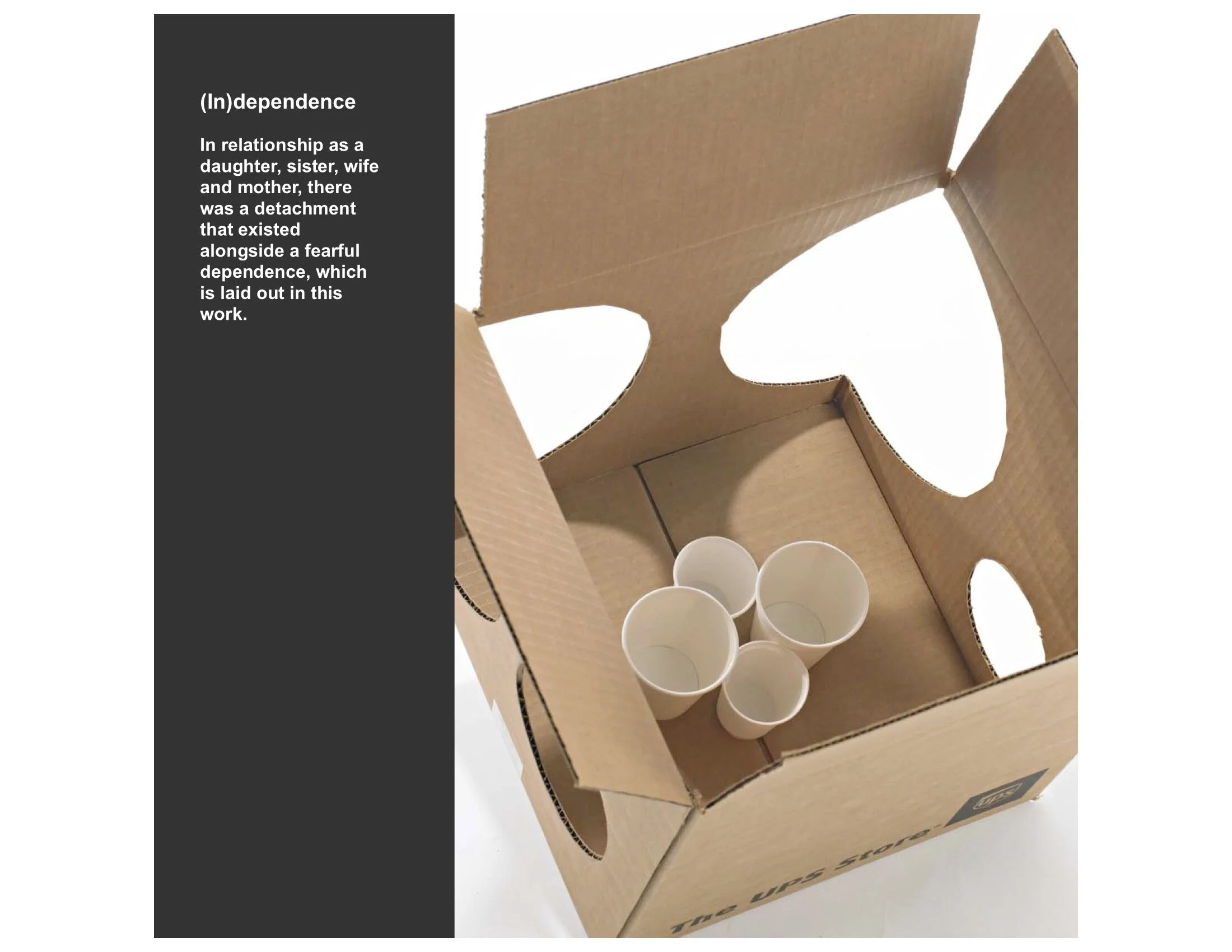

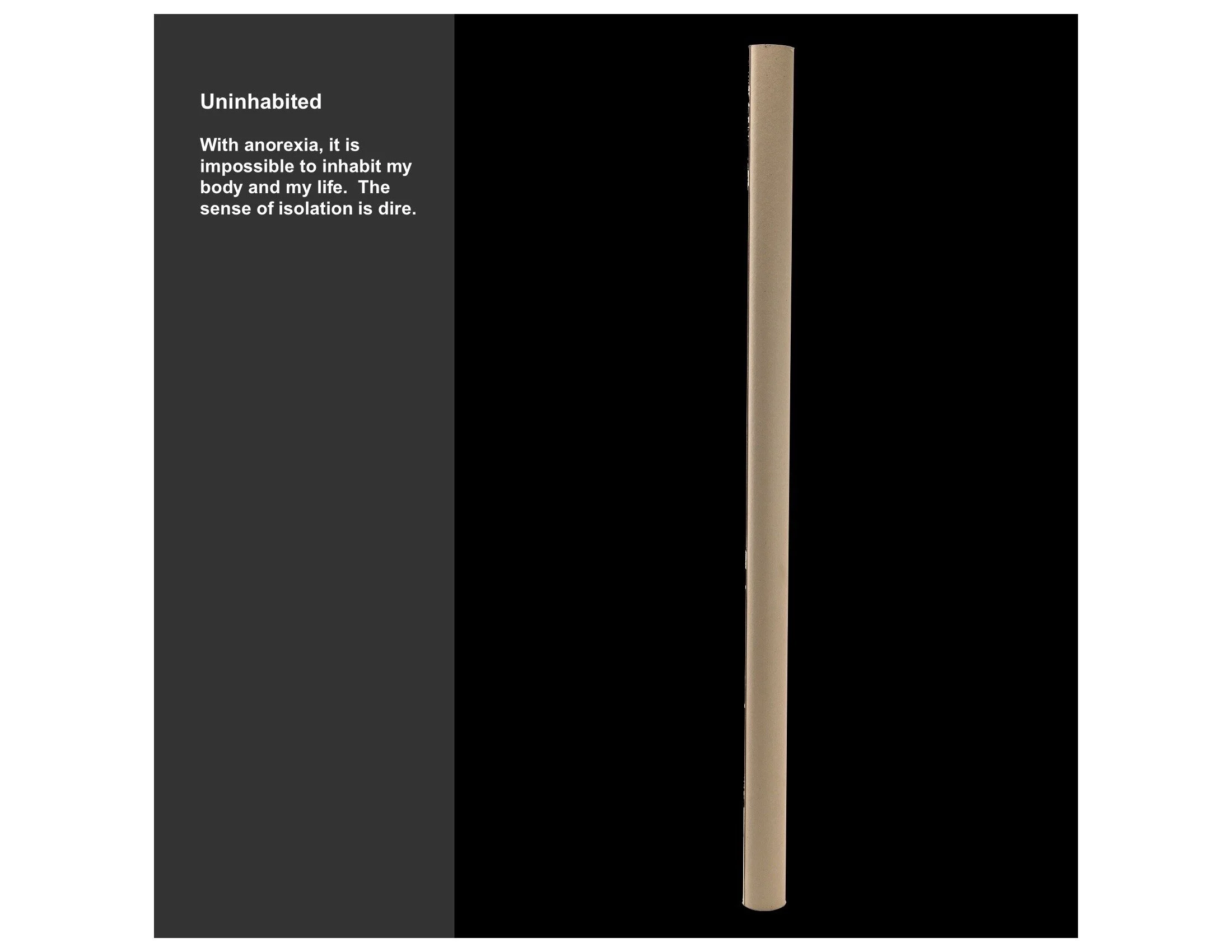

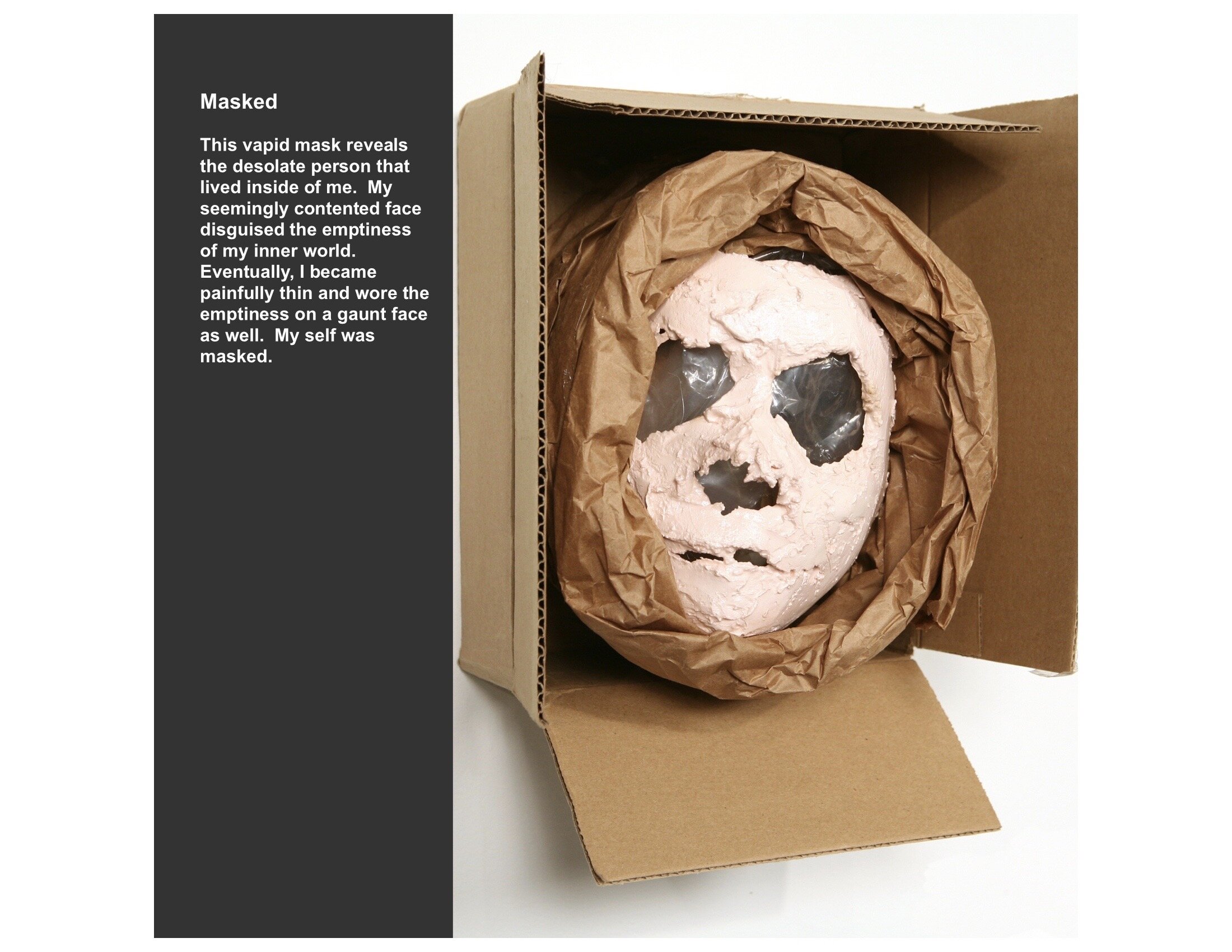

After the first piece, I was drawn to boxes as a medium for expression. Each one an abundant vessel. Other everyday materials began to grab me. I incorporate those that are raw and earthy in texture, shape and structure. The palette is neutral. The juxtaposition of simple materials with complex themes is intentional. The stark visual context draws the emotional intensity to the surface. Subtlety and boldness exist side-by-side. Descriptive text accompanies each piece, sharpening the work. Text and image have equal weight.

The pieces in this series were conceived and created during my recovery from anorexia. A visual representation of my illness first took shape while in residential treatment. Upon entering, each patient was asked to produce a written timeline of her life, highlighting significant dates and events that may have predisposed her to an eating disorder. I resisted what seemed to me a simplistic assignment. While I never sought help for my eating disorder before, I felt well beyond a cliché approach to the profound work that I knew lay ahead.

In the early stages, I had no idea what to expect in treatment. Nor could I ever have imagined needing it. I had many doubts and questions. What did recovery entail? What would happen to me? How big was I going to get? Eating what? Who were these people? I didn’t know anyone. They didn’t know me. Did anyone know me? Who was I besides my eating disorder? There was too much pain, fear and loneliness. I became too weak and too tired to contain it any longer. My seams were bursting. Edges were crumbling. What might be exposed - to others and myself?

As treatment progressed and other patients presented their timelines in therapy groups, I still had yet to do one. Spontaneously, an idea came to me for how to track the development of my eating disorder. I envisioned it was about what I looked like and what lay beneath the surface. It took the form of a life-size paper tracing of my body. Over time, the tracing evolved viscerally into a stand-up piece called Running on Empty. It did not contain dates and events, yet it revealed how anorexia had become embedded in every cell and every system of my body, dictating every action, every feeling and every thought. My eating disorder and I were wholly fused.

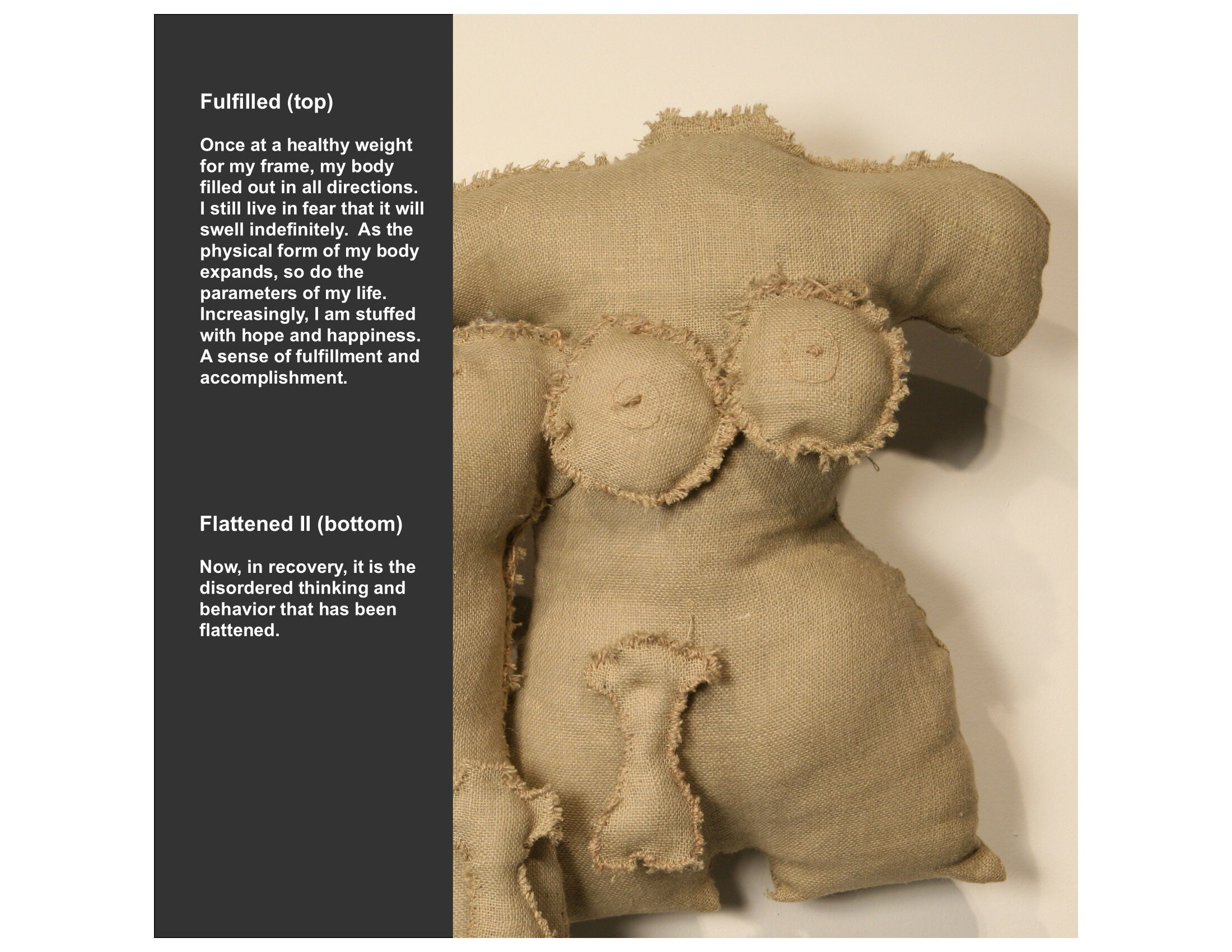

Well into recovery, a therapist asked if I were to do another image of myself what it might look like then. I knew it would be bigger and fuller. More dimensional and with more substance. My body had bigger dimensions and so did my life. Everything about me was fuller. I always felt boxy in my body and with 30 extra pounds even more so. I didn’t like feeling and looking like an even bigger box. This metaphor eventually became another medium for my art. After moving through residential and outpatient treatment, I began working with boxes as a way to depict aspects of my illness and recovery. The box offered a rich terrain for reflection. Looking inside a box, I recalled emotions, relationships, stages and events from my life. Thoughts and feelings that played out within my family of origin and later in my family through marriage.

While I had some awareness of the core issues underlying my anorexia, they repeatedly resurfaced throughout my therapeutic work. At times the therapy would drive the art and I would leave a session with a vision for a new piece. Other times, the art would inform the therapy and the creative process would result in greater personal insight. When an issue was central to my therapeutic work, the same issue emerged in a sculpture. The pieces became a valuable communication tool, providing a clearer understanding of my feelings and perceptions. More precise than words, the sculptures became a way to record my progress and keep me engaged in recovery. I continue to be drawn to boxes and everyday containers. I am lured by their limitless form and substance. Each one an abundant vessel much like my body.